Our lives are surrounded by computers, from the smartphones to the elevator controller, from the plane to the game consoles. They can do so many things, but how do we tell them what to do? This involves programming, and people writing the program in specific languages made to communicate with the computer. But where do these languages come from?

There’s C++, JavaScript, HTML… Where do they come from?

Programming languages are a way to express in text 1 how to perform a some tasks on a computer. Each language is different and has a set of tasks that they are better at, though most languages can do most tasks. For instance, HTML is very good to represent web pages, like the page you’re looking at, but it can’t make it interactive. JavaScript can add movement and reactions to a page. C++ can be used to build the web browser that you’re using to view the page, but it could also have been written in Java or Rust. So each language is created as needed, when we have some tasks that cannot be easily done with the existing ones.

// C++

class Shelf {

unsigned bottles_left_;

public:

Shelf(unsigned bottlesbought)

: bottles_left_(bottlesbought){}

void TakeOneDown() {

if (!bottles_left_)

throw NoMoreBottlesException;

--bottles_left_;

}

operator int () { return bottles_left_; }

};

How does the computer understand languages?

Computers even today execute simple instructions: add 2 numbers, move this number there and so on. Surprisingly, this is enough to react to a user pressing keys on a keyboard, connect to internet or play a videogame. But how do computers know what to do? To better understand, let’s go back to the early computers of 1930.

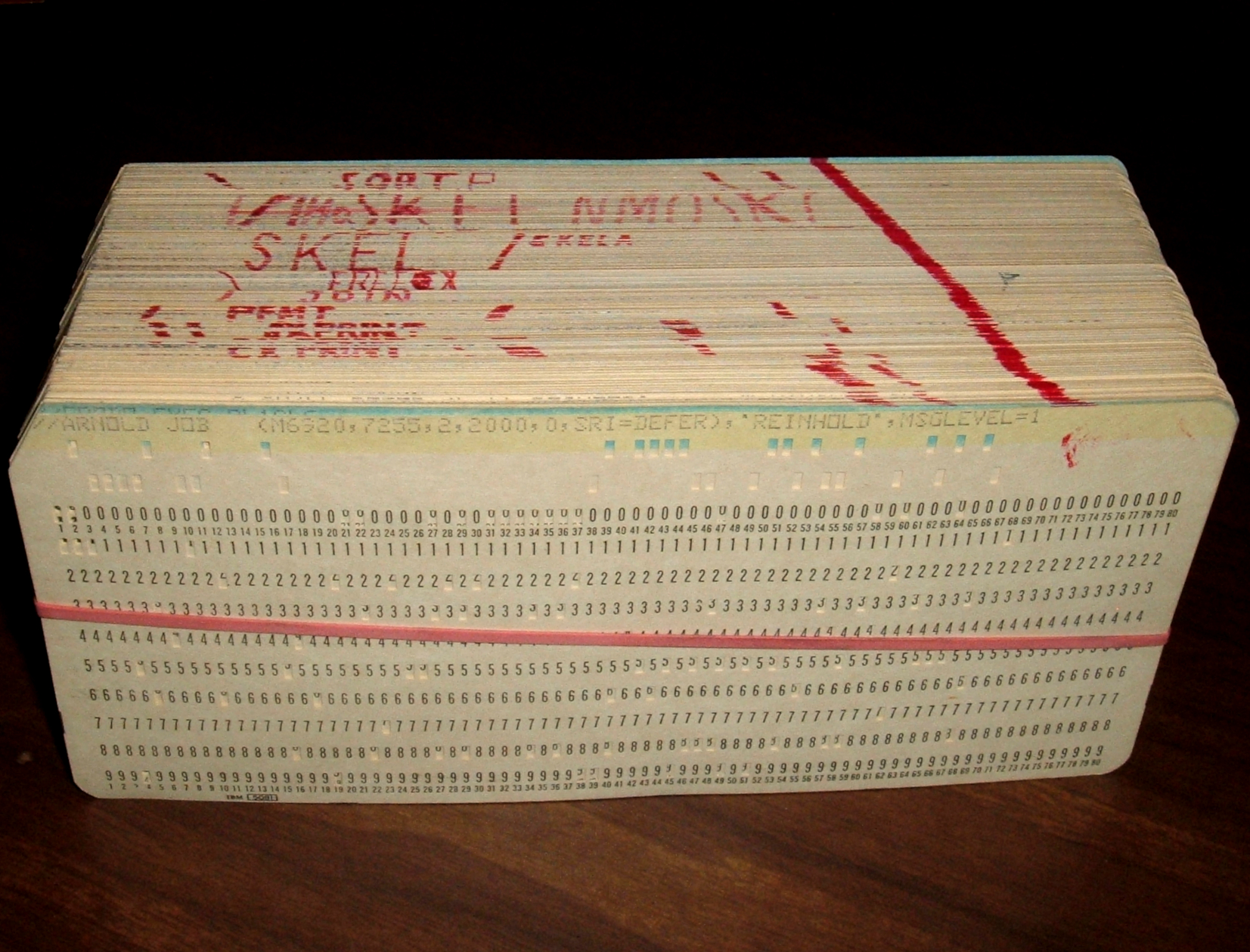

At the time, the computers were huge expensive beasts. They did not have keyboards or hard drives, so the way they could know what to do was to physically give them a program to run, a series of operations. These were written on punch cards: you would punch a hole on the first column for the first instruction, one on the second for the second instruction and so on. The line of the hole would determine what the instruction was: if the hole is in the first column, add two numbers; in the second column, multiply them. In a way, they were similar to the barrel organs that you sometimes see in amusement parks, with their score sheets full of holes.

Of course, nowadays we don’t have punch cards anymore: the instructions are written on your hard drive and the computer reads that. The hard drive contains a lot of bits, either 0 or 1. But it’s still essentially the same thing, only with bit patterns: if the computer reads 110100, it’ll add two numbers, 001011 means multiply.

# Python

def is_prime(num):

if num == 1:

return True

elif num > 1:

for i in range(2, num):

if (num % i) == 0:

return True

return False

def main():

if is_prime(29):

print("29 is prime")

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

Who decides what the instructions are?

That’s the role of the one who makes the computer: the electrical circuits in your computer are made so that when they see 110100, they will add two numbers. But it’s only a convention! Two computers built differently will interpret those bits differently. This is part of the reason why you can’t take a Windows “program.exe” and run it on a Mac. It’s like giving a Russian book to someone who speaks only Spanish, it doesn’t make sense to the Mac, the words are in the wrong language. But take a Windows program and copy it to another Windows machine, and it will (mostly) work, because they speak the same language.

Okay, but where do the other languages come from?

Right, now that we know that computers only execute their own language of instructions, the rest is just a matter of translation. The computer on its own doesn’t understand C++ or HTML. For this, we have a program called a “compiler” or “interpreter” that will do the translation. For instance, you might write “1+2” in C++, and the compiler will write the instruction 110100. “1+2” is much easier to remember for us, and much easier to read. That also allows us to write much more complex languages: in HTML you can easily say “draw a big red rectangle”, but it’s very long to say in instructions. People wanted to be able to write “draw a big red rectangle”, so they wrote an interpreter that translates that into instructions. For HTML, that interpreter is your web browser. It’s actually such a matter of convention that different browsers don’t speak exactly the same language, even though they agree on most things: some websites will work on one browser, but not on others because they use a word that the other browsers don’t know, or which means a different thing to them.

Similarly, the browser itself is a complex program. It was written (mostly) in C++, and then compiled to instructions. But the compiler is a complex program as well, translating C++ is complicated. So it was written in C, a simpler language. The compiler for that was written… in C as well! A simpler version of C. The compiler for this one was so simple that it could be written in assembly, which translates directly into instructions.

💻 ⇒ instructions ⇒ assembly ⇒ (simple) C ⇒ C ⇒ C++ ⇒ browser

Another way to look at it is the evolution that led to the browser:

- The computer maker creates electrical circuits which understand the simple language of instructions.

- They write a very simple translator from assembly to instructions. Assembly is just a textual representation of instructions, so the translation is easy.

- Then someone else writes a very simple C compiler in assembly. Writing assembly is annoying and specific to the computer, but C is friendlier and can be translated to the assembly of any computer.

- With this C compiler, people can write more complex programs. But it can be difficult to manage big projects in C, so someone writes a more complex language, C++, along with its compiler in C.

- Using C++, we can now create very complex programs, like the browser. The same C++ code gets translated differently for Windows, Mac, Linux and so on.

; Lisp

(defun is-prime (n &optional (d (- n 1)))

(or (= d 1)

(and (/= (rem n d) 0)

(is-prime n (- d 1)))))

How do you create a language?

As we saw just above, the only thing you need for a useful computer language is an interpreter or a compiler. It’s all a matter of translation. Some languages have international standards defining what you can write in them, but others are just “whatever the compiler accepts”. Anyone can create a compiler for the language they want; a lot of languages are completely unknown because very few people use them, or the compiler was never finished, or it was just a toy project to show what a language can do. On the other hand, some languages are very popular, and several compilers exist for the same language, like C++ or Java. Again, like the browsers, they understand slightly different languages, but agree on almost everything.

How many programming languages are there?

It depends how you count. If you count languages that have at least one user (the creator), then there are tens of thousands of languages! Even “published” languages that are available online number at least 1500: the website 99-bottles-of-beer.net lists programs that print the lyrics to the song “99 bottles of beer on the wall” in that many different languages. Even if you limit yourself to languages that are being used today in thriving businesses, you’ll easily find more than a hundred.

NB. Game of life in APL

life ← {⊃1 ⍵ ∨.∧ 3 4 = +/ +⌿ ¯1 0 1 ∘.⊖ ¯1 0 1 ⌽¨ ⊂⍵}

Why are there so many languages?

Each language tries to solve a different problem, or the same problem in a new way. HTML is good at drawing rectangles, but cannot make moving things. C++ can make almost anything, but it’s very complex. Prolog can solve logical problems, but cannot make a full program. Python can be used for a wide range of tasks, but is often slower than C++. Some languages are “general purpose”, you can do almost anything in them (though not necessarily easily), whereas others are more custom-built: a language to design computer chips, a language to decorate your webpage, etc. Some languages are more powerful but riskier, others restrict your freedom in exchange for more safety. Some languages are supported everywhere, others on a single platform.

When you write an Android app, you will not use the same language that is used to program an airplane, or a datacenter.

// Kotlin

interface Base64Encoder {

fun encode(src: ByteArray): ByteArray

fun encodeToString(src: ByteArray): String {

val encoded = encode(src)

return buildString(encoded.size) {

encoded.forEach { append(it.toChar()) }

}

}

}

expect object Base64Factory {

fun createEncoder(): Base64Encoder

}

Who creates the languages?

When you look at successful languages, you have broadly three categories:

- Passion projects started by a single individual.

- Research languages coming from a university.

- Practical languages created by a company.

Often, these languages (or rather their compilers) end up being free, and open-source: anyone can see how they are written, and can propose changes to them.

For passion projects, they benefit from the extra help by the community.

For research languages, having many users can help validate their research, and is a source of pride for the university.

Practical languages mix the other two; in addition, getting more users often leads to a business advantage. More Android apps make Android phones better, so Google will invest in making Android more accessible. For them, it makes sense that creating an app should be free.

Similarly, the CPU makers will often contributes to main languages to help them translate to the new language of their new chip: that allows anyone to write a program for their new chip, making the chip more useful.

However, some specialized industries have languages created by a single company selling access to their compiler, as there is a lot of domain-specific knowledge encoded into it.

"Brainfuck

>++++++++[-<+++++++++>]<.>>+>-[+]++>++>+++[>[->+++<<+++>]<<]>-----.>->

+++..+++.>-.<<+[>[+>+]>>]<--------------.>>.+++.------.--------.>+.>+.

Conclusion

Overall, programming languages are a matter of convention: there is no underlying structure that is discovered like in mathematics, they are just tools that are built for a purpose. Different people create different tools, and many people contribute to making better tools, since it benefits everyone. This is one of the great successes of internet and the open source movement: sharing small improvement with the community, so that in the end we can build amazing things.

-

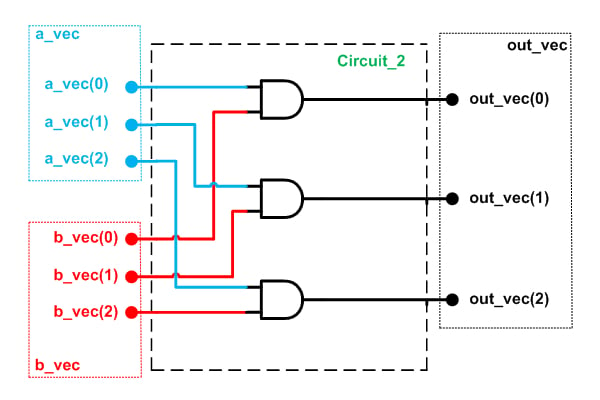

Some programming languages are not only based on text: some mix it with boxes and arrows (Unity), while others completely avoid text and are only visual (Verilog). ↩︎